Rain Rain, Go Away!

A good rainstorm in San Diego can be hard to come by. So when a series of storms come through the county and drench the land, as happened this year, there is much rejoicing…until the cool, wet weather begins to spread disease at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

In my job as Senior Research Associate with Disease Investigations, I conduct the post mortem exams (aka necropsies) on animals that have died at the Zoo and Safari Park. Recently a larger than normal number of hoofstock, mostly antelope like Kenya Impala, Blackbuck and Grant’s Gazelle, have contracted intestinal-related illnesses, some of which have been fatal. The cause in most cases? Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, a type of Gram-negative bacteria.

Infections of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis have been described worldwide as a cause of disease in sheep, cattle, goats, deer, and pigs, and is also a rare food-borne illness in people. Like E. coli and Salmonella, these organisms can be found in the environment, shed in the feces by asymptomatic animals in the herd, or carried by wild rodent or birds. We’ve seen a few cases of Y. pseudotuberculosis in native crows as well, which shows it can infect multiple taxa. This organism can survive and grow in low temperatures, hence why a cool rainy winter and spring in San Diego can lead to a rise in the number of bacterial intestinal cases we get.

In a fatal case, there are often characteristic lesions seen at necropsy that make us suspect Y. pseudotuberculosisis the cause. Small intestinal segments are thickened, red and inflamed. Mesenteric lymph nodes, usually about the size of a small grape, are prominent and sometimes golf ball to tennis ball-sized. At this point, a culture of a lymph node or intestinal content is submitted to the lab for confirmation that Y. pseudotuberculosisis the culprit.

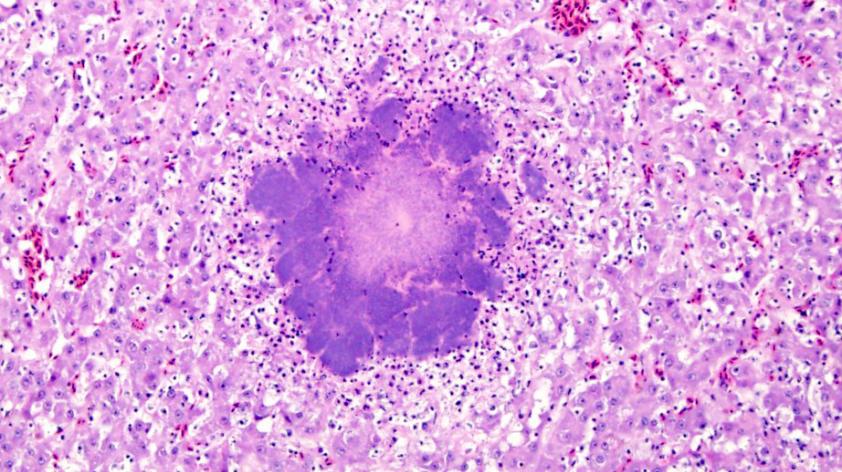

Examining tissues microscopically, the pathologists see large numbers of Gram-negative coccobacilli forming microcolonies throughout affected tissues. Inflammatory cells respond to form microabscesses around the bacteria. Similar abscesses may be present in lymph nodes, liver, lungs, and other organs depending on the spread of the infection.

So what can we do to protect the welfare of our animals? It starts with our amazing keepers, who help clean up the rain soaked fields (not easy when flooded pools form!) and perform daily checks on the large herds of hoofstock, identifying any animals that seem a bit “off.” The signs can be subtle, especially since these prey animals are good at hiding their illnesses. Keepers alert the vet staff to any lethargic or isolating animals, and often the first and only sign is dehydration. Rapid, aggressive fluid and antibiotic therapy is important for survival, so the information we provide from a necropsy is critical as the first alert of a developing outbreak.

For now, let the summer sun come!